Changes to the computing curriculum in England, which arrived last September requiring schools to teach bona fide programming skills to kids as young as five, are shaking out into increased opportunities for edtech startups in the U.K.

Making learning to code accessible, fun and engaging is the jumping off point of London-based startup Code Kingdoms, which has today launched out of beta, after trialling its game for the past year with around 25,000 kids and 700 schools.

Its educational JavaScript teaching software targets the six- to 13-year-old age-range, and can be played either as a web app via the Code Kingdoms’ site, or as an iOS app.

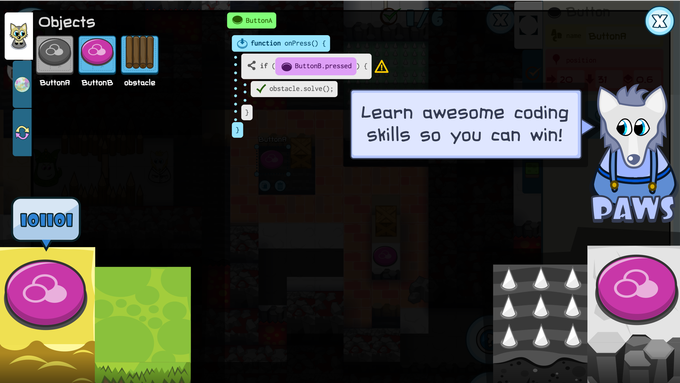

There are actually two versions of Code Kingdoms: one that’s free for schools to use, which strips out the gameplay element entirely so it becomes purely a simplified educational tool for teaching JavaScript; and another version that kids can play at home in their spare time which is first and foremost a game, albeit one that includes sporadic puzzle elements where kids have to use code elements to solve problems in order to progress in the game. So a sort of learning ‘lite’.

“Code Kingdom is a game that teaches kids how to code but in a way that is really fun for kids,” says co-founder and CEO Ross Targett. The premise being, he adds, that if you’re trying to entice kids digitally, your game has to be fun enough to wrestle their attention away from Minecraft — since you’re inevitably competing in that same “entertainment space”.

Using a game and game mechanics as a wrapper for teaching coding also brings native stickiness to the learning experience, says Targett, explaining that the team began by building a learn to code tool that “wasn’t really a game” and finding usage dropping off after what looked like good initial engagement.

“Those core things that games have — so these basic loops that mean you want to come back daily to collect your rewards, earning a currency or working towards a goal… we didn’t have those — so what we were having is really good engagement for a few hours and then no one coming back because it didn’t really have the mechanism to do so. So we went back to the drawing board and made sure the game was actually very powerful. But the original coding tool we built to get kids coding is still a fundamental part of it.”

The idea for building Code Kingdoms followed on from Targett and his co-founder spending time volunteering in schools teaching kids programming, as part of corporate social responsibility programs when they worked for Intel and ARM. In schools they were using the MIT graphical programming language Scratch, but spotted what they saw as an opportunity to update Scratch’s approach — and teach a real programing language, rather than a pseudo-language.

“Most things out there are designed for teachers, or for how adults perceive kids to be learning — nothing’s really designed to make it really fun for kids, so we wanted to make it super fun for kids so they get excited about learning to code computer science, and then hopefully go on because they’re excited to actually explore it as a career, or look at it in other subjects,” says Targett.

He argues that Scratch is no longer up to scratch for England’s schools as it does not teach a real programming language — which is a requirement of the new curriculum. He also reckons it’s pretty dated now, having being built for an earlier, desktop computing world, rather than the modern mobile-focused space.

Other relatively new entrants in the ‘teach kids coding’ space include U.K. startup Kano, which involves both DIY hardware and learn to code software, and similarly offers a graphical interface to simplify programming. But Targett argues Kano is a platform on which the Code Kingdoms product could happily sit. So doesn’t seem them as like-for-like competition.

He says Code Kingdoms is also working with various other learn to code outreach organisations, such as Code Club and Teach First, to get its product into kids’ hands. “We find we complement more people than compete with them, and Kano’s a really good example of that,” he adds.

Of course it is also possible to learn Java coding via making Minecraft mods, but Targett reckons that’s “quite a step up” in terms of ability required. “We want to bridge that gap, enable anyone to get excited, learn the skill without that massive aptitude you need to really get started,” he adds. “And Minecraft was never designed to teach kids to code.”

While Targett and the team are undoubtedly evangelical about teaching kids coding, they are also entrepreneurs with dreams of building a big, profitable business so Code Kingdoms is not a not-for-profit. There is very much a business plan here.

So, while it’s giving its software to schools for free, it’s aiming to monetize via the play-at-home game version of the product — using schools as its low-cost distribution mechanism to get in front of lots of kids’ eyeballs. In future it plans to sell premium content for the non-schools version of its software to kids’ parents, says Targett.

“We see schools as a channel to acquire users,” he notes. “The kids will discover the product in their class and then they’ll go home and play… We thought this was a really good way to acquire users very cheaply that are very engaged. And use schools as a promotional channel. Because it’s free we get more schools, more teachers engaged. We get a lot of goodwill from our teacher community.”

It’s also a pretty delicate balancing act when free educational software at school morphs into a money-hungry parent pesterer at home. But that’s the balance Code Kingdoms is aiming to strike. “We plan to have premium content in the app which is non-educational, it’s more entertainment focused, so a kid that doesn’t want to spend money can still learn,” adds Targett.

The startup has raised around $410,000 to date, including from U.S.-based seed fund SparkLabs Global Ventures, which Targett dubs pre-seed funding — given the large amounts required to fuel a gaming startup. He says it will be looking to raise a larger round in June.

Its short term focus is squarely on the U.K. market, with educational content tailored to the U.K. curriculum, but the aim is to expand the product to the U.S., South Korea and then elsewhere in Europe down the line.